California water district going to extreme lengths to make every drop count

July 25, 2022

AWWA Articles

California water district going to extreme lengths to make every drop count

A parched water system in Los Angeles County, faced with an extreme drought emergency and severe water restrictions across the Southern California region, is pulling out all the stops to make every drop of water count.

A parched water system in Los Angeles County, faced with an extreme drought emergency and severe water restrictions across the Southern California region, is pulling out all the stops to make every drop of water count.

The Las Virgenes Municipal Water District (LVMWD), which provides 75,000 customers with potable water, wastewater treatment, recycled water and biosolids composting, also offers free recycled water for irrigation, free compost, a customer portal to track usage, a native California demonstration garden, and a discounted irrigation controller program. The district has nearly completed a year-long transition to smart water meters. (Pictured above, climate change is causing drought and wildfires, such as this one in Los Angeles County that threatened the LVMWD headquarters building in 2018.)

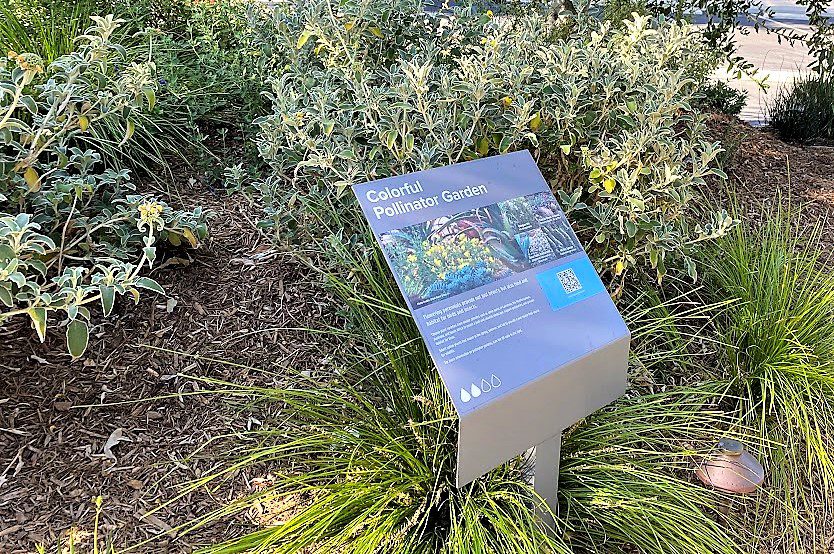

During an earlier 2015 drought, LVMWD implemented a system that assigned a water budget specific to each customer, based on household size and the configuration of their property. The outdoor-use use portion of that budget was reduced by half this April, due to the drought emergency. (Pictured left, demonstration garden shows sustainable foliage.)

During an earlier 2015 drought, LVMWD implemented a system that assigned a water budget specific to each customer, based on household size and the configuration of their property. The outdoor-use use portion of that budget was reduced by half this April, due to the drought emergency. (Pictured left, demonstration garden shows sustainable foliage.)

“Broadly speaking, our strategy is to give customers the tools to be engaged in how they use water and to determine what is the right amount, along with the flexibility to use it as they wish,” said David Pedersen, LVMWD general manager. “In the current drought emergency, there are extra rules in place on top of that because we are part of the State Water Project dependent area within Metropolitan Water District’s service territory and subject to its emergency water conservation program.”

“Broadly speaking, our strategy is to give customers the tools to be engaged in how they use water and to determine what is the right amount, along with the flexibility to use it as they wish,” said David Pedersen, LVMWD general manager. “In the current drought emergency, there are extra rules in place on top of that because we are part of the State Water Project dependent area within Metropolitan Water District’s service territory and subject to its emergency water conservation program.”

LVMWD has very little access to groundwater and its main water supply comes from the State Water Project in Northern California, which is dangerously low after the state’s driest-ever start to the year. Since June, the district’s water allocation from wholesale supplier Metropolitan has been reduced by 73% and its customers have been limited to no more than one watering day a week.

“We’ve never had an allocation reduction that was even close to this in 64 years of operations,” Pedersen said. “We’re doing a great job but still not meeting the numbers, and we need to do a lot more.”

Tamping down water usage

On average, the district’s customers used 205 gallons per person per day in 2021, 70% for outdoor use – a far cry from the district’s goal of 80 gallons per person per day.

A unique challenge is that some of the district’s customers live in multimillion dollar mansions with lush and extensive landscaping. Although anyone who exceeds 150% of their water budget for at least two months pays a penalty, that may not be much of a deterrent for some of these customers who aren’t as price sensitive.

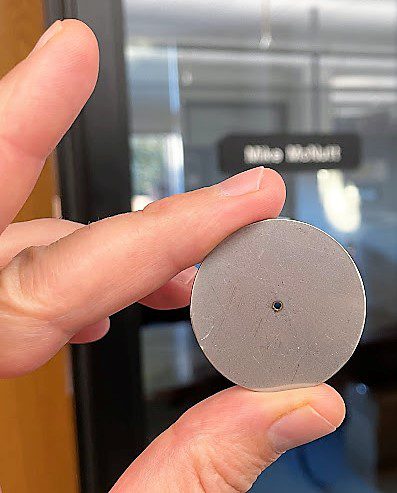

To tame the usage of customers who repeatedly exceed their water budgets, the district has begun using a custom-built water flow restrictor (pictured left) as a solution of last resort. The small metal device, designed by LVMWD senior field customer service representative Cason Gilmer, is installed at the main shutoff valve of a home or business.

To tame the usage of customers who repeatedly exceed their water budgets, the district has begun using a custom-built water flow restrictor (pictured left) as a solution of last resort. The small metal device, designed by LVMWD senior field customer service representative Cason Gilmer, is installed at the main shutoff valve of a home or business.

When inserted, the water flow restrictor slashes water flow from 30 gallons to less than one gallon per minute. While indoor use remains adequate, there isn’t enough pressure for lawn sprinklers. There is a $2,500 fine for tampering with or removing the device.

Customers who haven’t reduced their water usage from December 2021 and have exceeded 150% of their monthly water budgets at least four times are first given an opportunity to sign a water usage commitment form to reduce their usage. This includes allowing for a water survey to be completed at the customer’s home by district staff to identify where water can be saved, installing a weather-based irrigation control device, and acknowledging the drought and water supply conditions.

“The drought situation is so severe that you cannot just pay more to use more,” Pedersen said. “We can’t have a small segment of our community not doing their part. The flow restrictor is sort of the equalizer.”

Finding long-term solutions

These efforts are not just for the short-term, Pedersen stressed. “We can’t just bounce right back to the way things were after this drought emergency, then have it happen again,” he said. He listed some LVMWD strategies to increase local water supply reliability:

These efforts are not just for the short-term, Pedersen stressed. “We can’t just bounce right back to the way things were after this drought emergency, then have it happen again,” he said. He listed some LVMWD strategies to increase local water supply reliability:

- Create an affordable source of local water supply through potable reuse. The district is partnering with Triunfo Water & Sanitation District to develop the Pure Water Project Las Virgenes-Triunfo (pictured right is the demonstration project). The goal of the project is to deliver recycled water to an advanced water treatment facility to further purify the water, eliminate discharging recycled water into Malibu Creek, and create a new local water supply.

- Support efforts to expand Metropolitan Water District’s infrastructure so it can deliver water to LVMWD from Diamond Valley Lake and the Colorado River Aqueduct.

- Support increased investment in the State Water Project to improve storage, conveyance, supply, and climate change adaptations.

“None of the effects from climate change that we’re seeing are surprising – snowpack not resulting in runoff, flooding, extended drought, increasing temperatures, wildfire and rising sea level. What we didn’t plan for is how quickly these effects are happening,” Pedersen said.

“We are feeling the impacts and needing to adapt in real time while planning for the future,” he added. “A lot of our 20th Century infrastructure wasn’t designed to be flexible enough to handle the extreme swings we’re seeing, from periods of extreme drought to flooding. I’ve never seen a more challenging time in water. Fortunately, that brings opportunity to rise to the occasion, but there’s quite a mountain to climb here.”

Advertisement